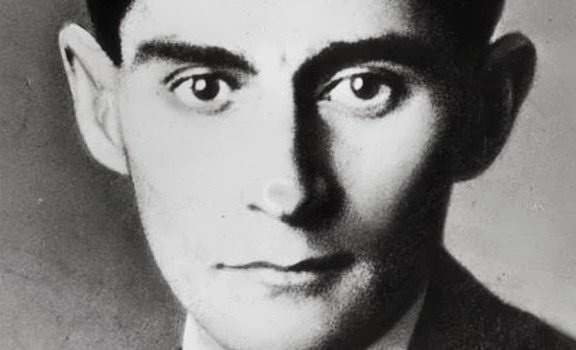

Franz Kafka © Schocken Books

"A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us."

When Franz Kafka wrote these now famous words to his friend Oskar Pollak in 1904, he unknowingly foreshadowed the impact of his as-yet-unpublished novella The Metamorphosis on a young writer reading him in translation as a university student in Bogotá, Colombia in the 1940s.

The influence of Kafka, born 130 years ago this week (July 3, 1883) in Prague, is great among twentieth-century writers from Albert Camus to Jorge Luis Borges -- the term Kafkaesque has even entered the vernacular as a way to describe events so bizarre they seem surreal -- but the transformation of his protagonist Gregor Samsa from alienated bureaucrat into a gigantic insect over the course of one morning seems to have had the most profound impact on the literary output of Gabriel García Márquez, who cites the story as inspiring his vocation.

In Living to Tell the Tale, published in 2003 as the first of three projected volumes of his memoirs, taking him from birth through the age of twenty-eight, the Nobel-winning author of magical realist novels One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera describes a night his roommate came in with three books he had just bought:

"...and he lent me one chosen at random, as he often did to help me sleep. But this time the effect was just the opposite: I never again slept with my former serenity. The book was Franz Kafka's The Metamorphosis...that determined a new direction for my life from its first line, which today is one of the great devices in world literature: 'As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.'...When I finished reading The Metamorphosis I felt an irresistible longing to live in that alien paradise. The day found me at the portable typewriter...attempting to write something that would resemble Kafka's poor bureaucrat changed into an enormous cockroach."

More succinctly in a 1981 Paris Review interview, he says:

"When I read the line I thought to myself that I didn't know anyone was allowed to write things like that. If I had known, I would have started writing a long time ago. So I immediately started writing short stories."

That Kafka had such a liberating influence is especially striking given the strong possibility that his writings could easily have never reached García Márquez. As he was dying in 1924 at the age of forty, Kafka famously demanded that his friend Max Brod, a fellow German-speaking member of Prague's Jewish community, burn all of his papers. Against his wishes, Brod published a selection of his manuscripts, bringing what is widely considered to be the most important body of work in twentieth-century German literature to the masses.

Late last year, a Tel Aviv judge presiding over a long-running trial over the ownership of the collection's remaining unpublished works ruled that it belongs to the Israeli National Library in Jerusalem. When the library publishes the documents online in the near future, there is bound to be a young writer somewhere in the world who will discover Kafka for the first time in those tens of thousands of pages. While we can only guess where he or she might be, we hope it is the site of a frozen sea ready to be cracked open.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario