by BELLE BETH COOPER

This post originally appeared on the Crew blog.

Whether you want to learn a new language, learn to cook, take up a musical instrument, or just get more out of the books you read, it helps to know how your brain learns.

While everyone learns slightly differently, we do have similarities in the way our brains take in new information, and knowing how this works can help us choose the most efficient strategies for learning new things.

Here are six things you should know about the brain’s learning systems.

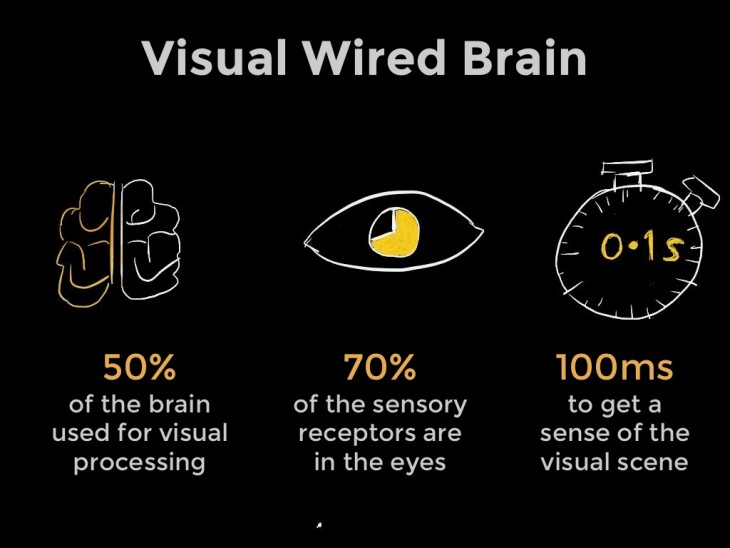

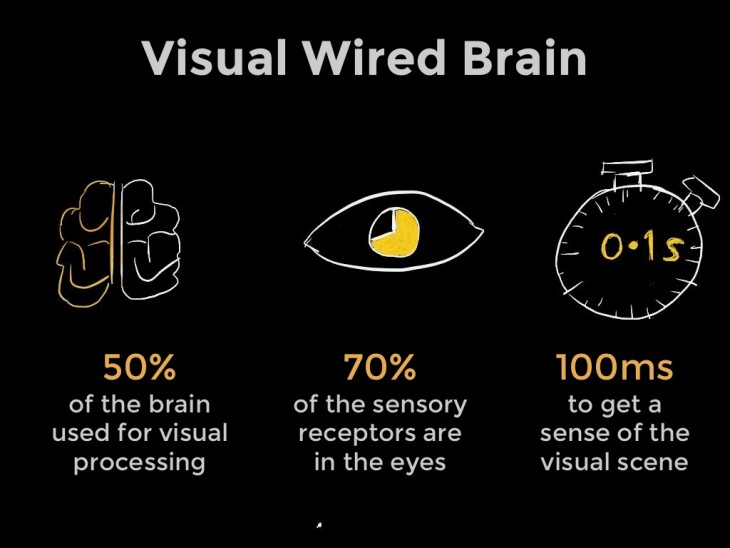

1. We take in information better when it’s visual

The brain uses 50 percent of its resources on vision.

Think about that for a minute. Half of your brain power goes to your eyes and the processes in your brain that turn what you see into information. The other half has to be split up among all the other functions your body has.

Vision is not only a power-hungry sense, but it trumps our other senses when it comes to taking in information.

A perfect example of this is an experiment where 54 wine aficionados were asked to taste wine samples. The experimenters dropped odorless, tasteless red dye into white wines to see whether the wine tasters would still know they were white based on the taste and smell.

They didn’t. Vision is such a big part of how we interpret the world that it can overwhelm our other senses.

Another surprising finding about vision is that we treat text as images. As you read this paragraph, your brain is interpreting each letter as an image. This makes reading incredibly inefficient when compared to how quickly and easily we can take in information from a picture.

More than just static visuals, we pay special attention to anything we see that’s moving. So pictures and animations are your best friends when it comes to learning.

Action: Find or make flash cards with images on them. Add doodles, photos, or pictures from magazines and newspapers to your notes. Use colors and diagrams to illustrate new concepts you learn.

2. We remember the big picture better than the details

When you’re learning lots of new concepts, it’s easy to get lost in the barrage of information. One way to avoid being overwhelmed is to keep referring back to the big picture. This is probably where you’ll start with something new, so coming back to explore how the new concept you just learned fits into that big picture can be helpful.

In fact, our brains tend to hang onto the gist of what we’re learning better than the details, so we might as well play into our brains’ natural tendencies.

When the brain takes in new information, it hangs onto it better if it alreadyhas some information to relate it to. This is where starting with the gist of an idea can be helpful: it gives you something to hang each detail on as you learn it.

I read a metaphor about this concept once that I loved: imagine your brain is like a closet full of shelves: as you add more clothes they fill up more of the shelves and you start categorizing them.

Now if you add a black sweater (a new piece of information) it can go on the sweater shelf, the black clothes shelf, the winter clothes shelf, or the wool shelf. In real life you can’t put your sweater on more than one shelf, but in your brain that new piece of information gets linked to each of those existing ideas. You’ll more easily remember that information later because when you learned it you related it to various other things you already knew.

Action: Keep a large diagram or page of notes handy that explains the big picture of what you’re learning and add to it each major concept you learn along the way.

3. Sleep largely affects learning and memory

Studies have shown that a night of sleep in-between learning something new and being tested on it can significantly improve performance. In a study of motor skills, participants who were tested 12 hours after learning a new skill with a night of sleep in-between improved by 20.5 percent, compared to just 3.9 percent improvement for participants who were tested at 4-hour intervals during waking hours.

Naps can improve learning just like a full night of sleep can. A study from the University of California found that participants who napped after completing a challenging task performed better when completing the task again later, compared to participants who stayed awake in-between tests.

Sleeping before you learn can also be beneficial. Dr Matthew Walker, the lead researcher of the University of California study, said “Sleep prepares the brain like a dry sponge, ready to soak up new information”.

Action: Try practicing your new skill—or reading about it—before going to bed or taking a nap. When you wake up, write some notes on what you remember from your last study session.

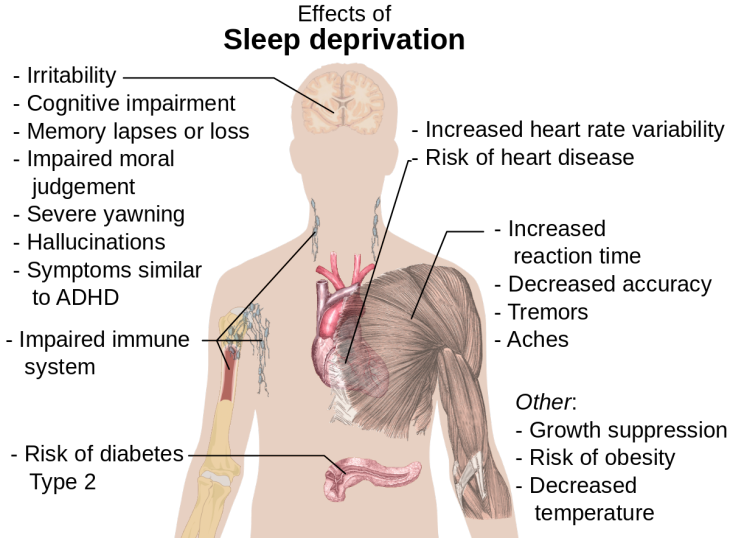

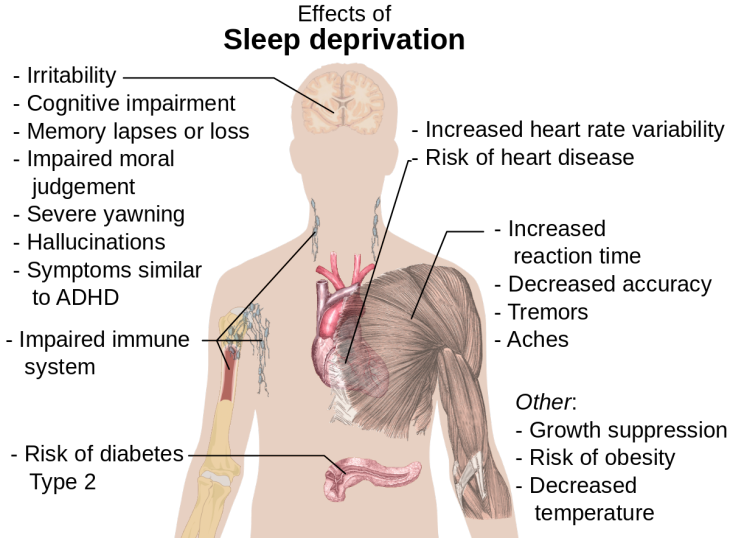

4. Sleep deprivation significantly reduces your ability to learn new information

Sleep deprivation is a scary thing. Because we don’t fully understand sleep and its purpose yet (though we have some ideas) we don’t always respect our need for sleep.

But although we can’t say definitively what sleep does for us, we know what happens if you don’t get enough. Sleep deprivation makes us play it safe by avoiding risks and leaning on old habits. It also increases our likelihood of being physically injured, since our bodies don’t perform as well when we’re tired.

Most importantly for learning: sleep deprivation can cut your brain’s ability to take in new information by almost 40 percent. Compared to getting a good night’s sleep and waking up refreshed and ready to learn, an all-nighter doesn’t seem worth the effort.

A Harvard Medical School study found that the first 30 hours after learning something are critical, and sleep deprivation during this time can cancel out any learning benefits of getting a full night’s sleep after those 30 hours are up.

Action: Forget all-nighters. Save practice and study sessions for days when you’re alert and well-rested. And definitely avoid sleep deprivation right after learning something new.

5. We learn best by teaching others

When we expect to have to teach other people what we’re learning, we take in new information better. We organize it better in our minds, remember it more correctly, and we’re better at remembering the most important parts of what we’ve learned.

One study told half the participants they would be tested on the information they were learning, and told the other half they would have to teach someone else what they learned. Both sets of participants were tested on the information and didn’t have to teach anyone else, but the subjects who thought they’d be teaching others performed better on the test.

The study’s lead author, Dr. John Nestojko, said the study implied that students’ mindsets before and during learning can make a big difference to how well we learn new information. “Positively altering a student’s mindset can be effectively achieved through rather simple instructions,” he said.

Though we don’t realize it, learning with the idea that we’ll have to teach this information later tends to invoke better methods for learning subconsciously. For instance, we focus on the most important pieces of information, the relationships between different concepts, and we carefully organize the information in our minds.

Action: Keep a notebook or blog where you write about what you’ve learned. Write about each new concept you learn as if it’s a lesson for others.

6. We learn new information better when it’s interleaved

A common learning approach is what UCLA researcher Dick Schmidt calls ‘block practice’. When you practice or focus on learning one particular thing over and over, that’s block practice. For instance, you might study history for a few hours in a row, or practice just your serve in a tennis lesson.

Schmidt advocates a different approach to learning called interleaving, which mixes up the information or skills you practice. Another UCLA researcher, Bob Bjork, studies interleaving in his psychology lab. One of his experiments involves teaching participants about artistic styles by showing them a series of images on a screen. Some of the participants are exposed to block practice of artistic styles (all 6 examples of a painter’s style are shown before moving on to another painter’s style), while others have their images interleaved (examples of different painter’s styles are mixed in together).

When the two groups are tested afterwards on how well they can recognize a painter’s style in a painting they haven’t seen before, the interleaving group usually scores around 60 percent, while the block group scores around 30 percent.

Surprisingly, around 70 percent of the participants in this experiment say they think the block practice was most effective in helping them learn. Clearly we have some work to do to understand what helps us learn best.

Bjork believes interleaving works better because it plays into our natural abilities to recognize patterns and outliers. When applied in the real world it also provides an opportunity for us to review information regularly, as we interleave what we already know with new information.

Some examples for interleaving could be cycling through three different subjects you need to study before exams, practicing speaking, listening, and writing skills of a foreign language in tandem rather than in blocks, or practicing your forehand, backhand, and serves in a single tennis lesson rather than setting aside one lesson for each.

Action: When you’re learning or practicing a new technique, practice it interleaved with other techniques. For instance, if you’re practicing a particular golf swing, practice other swings at the same time to mix it up.

If you’re learning new information, mix in information you already know—old vocabulary words and new when you’re learning a foreign language, for instance.

As Bob Bjork says, we all need to become smarter learners. “In almost any job, you have to keep managing some new kind of technology,” he said, so “just knowing how to manage your own learning is very important.”

Aunque cada uno aprende de forma totalmente distinta, tenemos similitudes en cuanto a cómo nuestro cerebro toma la información y saber cómo funciona ayuda a elegir las estrategias más eficientes para aprender cosas nuevas.

Tanto si quieres aprender un idioma, a cocinar, a tocar un instrumento o simplemente enterarte más de lo que lees, ayuda saber cómo aprende tu cerebro.

Aquí tienes 6 cosas que deberías saber sobre los sistemas de aprendizaje del cerebro:

Tanto si quieres aprender un idioma, a cocinar, a tocar un instrumento o simplemente enterarte más de lo que lees, ayuda saber cómo aprende tu cerebro.

Aquí tienes 6 cosas que deberías saber sobre los sistemas de aprendizaje del cerebro:

1. Tomamos mejor una información si es visual

El cerebro usa el 50% de sus recursos en la visión. Piénsalo por un momento. La mitad del poder de tu cerebro va a tus ojos y se procesa lo que ves en información. La otra mitad se divide entre las demás funciones que tiene tu cuerpo.

La vista no es solo un sentido hambriento de poder, sino que interrumpe a los demás sentidos cuando se trata de recoger información. Un ejemplo perfecto es un experimento en que se pidió a 54 aficionados del vino que probaran muestras de vino.

Aquellos que experimentaban con los catadores introdujeron tinta roja insípida en vino blanco para ver si los catadores sabrían diferenciar el vino blanco solamente por el sabor y el gusto. No lo hicieron. La vista es una grandísima parte de cómo interpretamos el mundo y puede turbar los demás sentidos.

Otro dato interesante es que tomamos el texto como imágenes. Mientras lees este párrafo, tu cerebro está interpretando cada letra como una imagen. Esto hace leer increíblemente ineficiente comparado con cuán rápido y fácil podemos tomar información de una imagen. Más que eso, tomamos especial atención a cualquier cosa que veamos en movimiento, así que fotos y animaciones son tus mejores amigos a la hora de aprender.

Acción: Usa cartas o cartulinas con imágenes. Añade fotos, dibujos, recortes de revistas y similares a tus apuntes. Usa colores y diagramas para ilustrar los nuevos conceptos que aprendas.

2. Recordamos mejor la imagen grande que los detalles

Cuando aprendes muchos conceptos nuevos, es fácil perderse en la información. Una forma de evitar que te sobrepase es partir de una gran imagen. Es probablemente donde empezarás, así que en cuanto avances, ver como el nuevo concepto encaja con la gran imagen te puede ayudar.

Cuando el cerebro toma una nueva información, se aferra mejor a ella cuando ya tiene almacenada una información relacionada. Es por eso que funciona la idea de la gran imagen, porque te relaciona los detalles con el concepto general.

Leí una metáfora sobre este concepto una vez, y me encantó: imagina que tu cerebro es un armario lleno de estanterías: en cuanto añades más ropa tienes que empezar a ordenar las estanterías por categorías. Ahora, si añades un jersey negro (nueva información) puede ir en la estantería de los jerséis o en la estantería de la ropa negra, en la de la ropa de invierno o en la de la lana.

En la vida real no puedes poner el jersey en más de una estantería, pero en tu cerebro esa nueva pieza de información se enlaza con cada una de las ideas ya existentes. Recordarás, pues, esa idea más fácilmente más tarde porque cuando la aprendiste la relacionaste con varios otros conceptos que ya sabías.

Acción: Ten a mano una larga pagina de diagramas que expliquen la “gran imagen” de lo que estás aprendiendo y añádele cada concepto mayor que aprendas a lo largo del camino.

3. Dormir mucho mejora al aprendizaje y la memoria

Los estudios han demostrado que una noche de sueño entre aprender una cosa nueva y examinarte puede mejorar significativamente tus resultados. En un estudio de habilidades motoras, los participantes examinados 12 horas después de aprender una habilidad con una noche de sueño de por medio lo hicieron un 20.5% mejor que comparado con el 3.9% de aquellos examinados en un intervalo de 4 horas. Las siestas pueden hacer el mismo efecto.

Un estudio de la Universidad de California vio que los participantes que habían hecho siesta después de completar una tarea lo hicieron mejor la siguiente vez que aquellos que se mantuvieron despiertos entre el primer y el segundo intento. Dormir antes de aprender también puede ser beneficioso.

Acción: Intenta practicar tu nueva habilidad – o leer sobre ello- antes de irte a la cama o tomar una siesta. Cuando te despiertes, escribe unas notas sobre lo que recuerdas de tu última sesión de estudio.

4. La privación de sueño reduce significativamente tu habilidad de aprender cosas nuevas

La privación de sueño no te favorece. Aunque a día de hoy todavía no entendemos bien el propósito del sueño, sabemos qué pasa si no dormimos suficiente. Privarte de sueño te hace ir sobre seguro siempre, evitar riesgos y quedarte con los antiguos hábitos. Eso incrementa la posibilidad de herirte porque nuestros cuerpos no funcionan bien cuando están cansados.

Y más importante aun para aprender: la privación de sueño puede cortar la habilidad del cerebro de tomar nueva información hasta casi el 40%. Comparado con dormir bien por la noche y despertar refrescado y preparado para aprender, el esfuerzo de no dormir parece no merecer la pena.

Un estudio de la escuela médica de Harvard vio que las primeras 30 horas después de aprender algo son críticas, y la privación de sueño durante este tiempo puede cancelar cualquier cosa que hayamos aprendido.

Acción: Déjate de noches en vela. Estudia y practica durante el día, cuando estás alerta y descansado. Y definitivamente evita no dormir justo después de aprender algo nuevo.

5. Aprendemos mejor enseñando a otros

Cuando tenemos que enseñarle a alguien lo que hemos aprendido, interiorizamos mejor la información. Organizamos mejor en nuestra mente, recordamos de forma más correcta y nos quedamos con las partes más importantes.

Un estudio les dijo a la mitad de participantes que serían examinados y a la otra mitad que tendrían que enseñar a alguien lo que habían aprendido. Ambos grupos fueron examinados, ninguno tuvo que dar ninguna clase, pero aquellos que pensaron que iban a tener que explicárselo a alguien lo hicieron mejor en el test.

Aunque no nos demos cuenta, aprender con la idea de que vamos a tener que enseñar esta información más tarde tiende a hacernos usar mejores métodos de aprendizaje de forma inconsciente. De hecho, nos centramos en las cosas más importantes, las relaciones entre conceptos y organizamos mejor la información mentalmente.

Acción: Ten una libreta y escribe lo que has aprendido. Escribe sobre cada nuevo concepto que aprendas como si la lección fuera para otro.

6. Aprendemos nueva información mejor cuando está intercalada

Cuando practicas o te centras en aprender una cosa particular una vez y otra y otra…eso es práctica en bloque. Es algo que puedes hacer cuando estudies historia o practiques un saque de tenis. Luego, hay otra forma, el intervalo, que mezcla la información o habilidades que practiques.

Un experimento relacionado tiene que ver con enseñar a los participantes de un estudio algunos estilos artísticos enseñándoles una serie de imágenes en una pantalla. Algunos de los participantes son expuestos al bloque (los ejemplos de un artista se muestran antes de pasar al siguiente artista), y otros a las imágenes intercaladas (ejemplos de diferentes artistas mezcladas).

Cuando los dos grupos se examinan (a parte de lo bien que puedan reconocer el estilo de cada artista) con una pintura que no han visto nunca antes, el grupo que ha aprendido de forma intercalada suele hacerlo un 60% mejor que el grupo que ha aprendido en bloque.

Sorprendentemente, alrededor del 70% de los participantes de este experimento dicen que creen que la práctica del bloque es más efectiva y les ayuda más a aprender. Claramente tenemos mucho trabajo que hacer para entender qué nos ayuda más a aprender.

Acción: Cuando estés aprendiendo o practicando una nueva técnica, practicala de forma intercalada con otra técnica. Si practicas un swing de golf en particular, practica otros swings mezclándolos.

Si estás aprendiendo nueva información, mézclala con otra que ya sepas. Las palabras antiguas del vocabulario y las nuevas, por ejemplo, aprendiendo un nuevo idioma. Como dijo Bob Bjork, todos necesitamos convertirnos en aprendices más listos. “En casi cualquier trabajo, debes usar algún tipo de tecnología, así que es importante saber cómo aprende uno mismo.”

Via TNW

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario